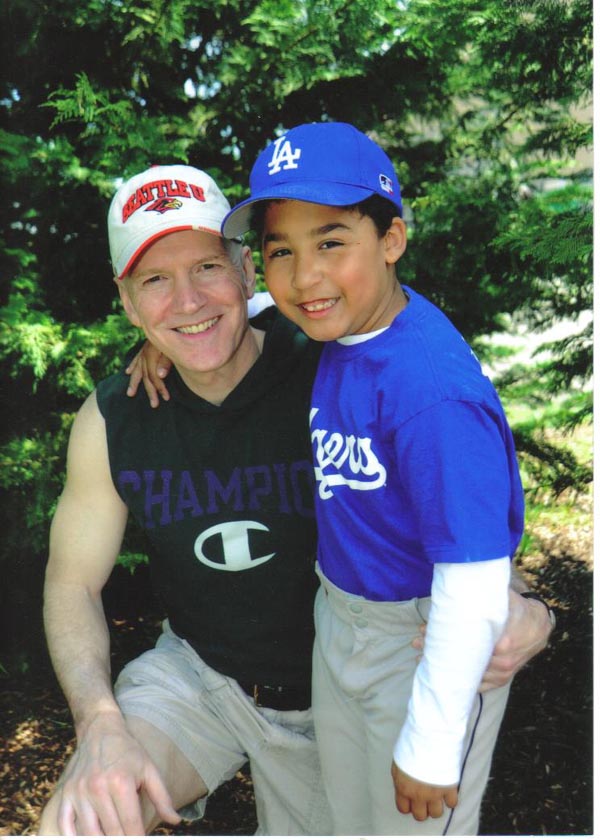

CLAY MOYLE AND SON CALEB

RUSSELL WILSON

I’ve been hearing some interesting reports over the past couple of days as a result of the fallout from the Seahawks trade of Percy Harvin. The latest comes from Mike Freeman of Bleacher Report in which he claims that it appears the root of the problem was a poor relationship between Harvin and Russell Wilson. In his report, Freeman claims there are other players who have problems with Wilson as well.

There were three different reasons given for some players’ problem with Wilson. One was that he was too close to management. Another was that he doesn’t always take the blame for his mistakes. But, it was the third and last reason given that has really garnered the most attention. That was one that Freeman feels is backed up by discussions with “several interviews” with Seahawk players, and it’s that some of his black teammates don’t believe Wilson is black enough, in Freeman’s words.

Robert Littal of Black Sports Online responded to Freeman’s article with one of his own that included the following comments:

“The not being black enough issue is ridiculous and something that black people in general need to stop harping on because it holds us back as a race. Yes, we are black, but we are also individuals that are free to have our own personality and tastes.

”The players who have that issue with Wilson, in my mind, are dumb and need to get over it. If Russell Wilson is comfortable being who he is, that is too bad you don’t think he is black enough. That shows your ignorance as an individual and you need to grow up.

“Black people in general have asked for centuries just for a fair shake, to be able to just be individuals that aren’t stereotyped and typecast as soon as we walk in the door.

“It is infuriating to me that we fight for that equality and still stereotype ourselves in the most simplistic forms, and if someone doesn’t meet that standard they aren’t ‘black enough.’”

Some of this hits home with me because I have a 16-year-old daughter who is African-American. Not long ago, I was driving her and a friend, who also happens to be African-American, somewhere and overhead a conversation they were having. Both have been raised in households with two caucasian parents and I’m sure that’s something that isn’t anywhere as unusual as it once was.

In any case, one of them brought up the fact a black student had recently asked them why they talked the way they did. Evidently, this was something they’d both been questioned about on more than one occasion by other black students at school.

My wife told me that my daughter said the first time she was asked that question at school she was confused and she asked the other party what they meant.

“Like a white person,” the other party replied.

Anyway, as my daughter and her friend compared notes on that type of experience during the car ride, one or the other said that they thought the next time they were asked why they talked the way they do they should just reply with an answer like, “because I’m well-spoken.”

They laughed together at the thought they should talk in a specific manner or use certain slang simply because of their race.

I hope they’ll always be comfortable enough to carry that attitude going forward. I’d hate to think that either will ever succumb to any kind of pressure to speak or behave in any manner that is unnatural simply to fit into any other parties preconceived expectations.

But, that said, I do understand we live in a world where all kinds of stereotypes exist. I’ve tried to explain to my daughter that the fact she’s African-American will mean that she’ll suffer from discrimination in many ways. I’m sure she’s been sheltered from that to a large degree growing up in the household she has.

One day I sat her down and tried to give her some examples of some things she might experience and some situations to be careful about putting herself in. For example, I told her that she shouldn’t be surprised to learn that she could find herself under greater scrutiny when walking through a store as an African-American than she might if she were caucasian.

o my surprise, she was already well aware of that. She proceeded to share a story with me about going to a department store with her mother where they got split up. She came across a necklace she thought her mother might like, so she picked it up and started to walk over to where her mother was shopping to show it to her. An older white woman immediately stopped her and asked her if she was going to buy that necklace. My daughter said she was going to show it to her mother. The woman asked her where her mother was and when my daughter pointed to the white lady across the store, the woman told my daughter that she didn’t believe her.

So, I imagine my daughter is probably nowhere near as naïve as I feared but I’m sure there will be many more lessons to be learned as she continues her journey through life.

I’ve had a number of friends of a different race throughout my life, whether they were African-American, Filipino, or some other race, and when I think about it I can remember a number of times where some of those individuals would speak or behave differently around me in a one-on-one situation than they would when they were among a group of individuals of their own race.

But, then again, I could say the same thing about many members of my own race, i.e., they would speak or behave one way in a one-on-one situation with myself, and then suddenly speak or behave much differently in a crowd.

Ultimately, it would be nice if everyone were comfortable enough to just be themselves under any circumstance and others could just accept them for who they are.

While looking for some materials related to this subject today, I came across an on-line interview that took place with Russell Wilson this past July. In the article, Wilson reflected upon joining the Seahawks:

“When I joined the Seahawks, I remember walking into the huddle and seeing all the different faces. Here I am 23, an African-American, a strong Christian. Our center, Max Unger, is from Hawaii. Our running back, Marshawn Lynch, is African-American, from the inner city in Oakland.

“Zach Miller, the tight end, is a white guy from Phoenix. I don’t care if they’re white, black, Christian, Jewish, atheist. It has no effect on how I view them. They’re there for me. I’m there for them. All I want to know is: Are they great teammates?”

Wouldn’t it be great if more people had that kind of attitude?