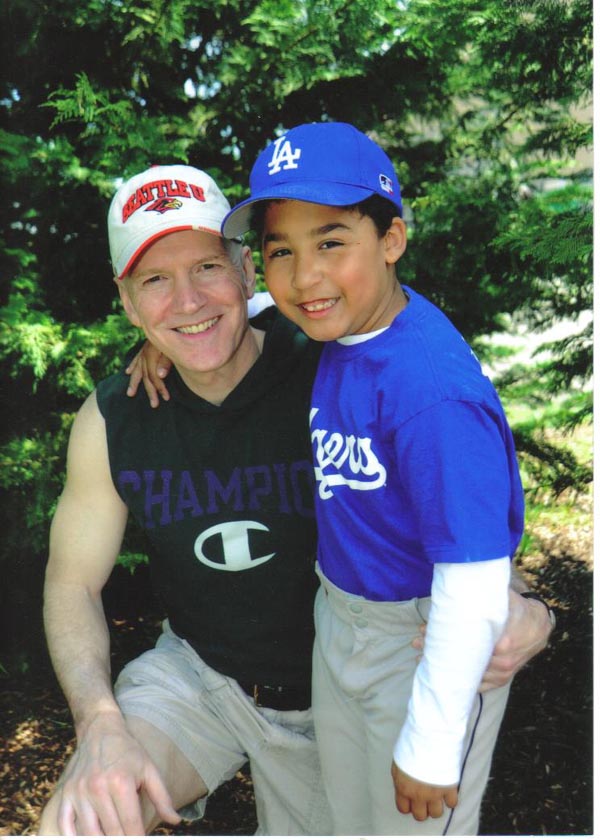

CLAY MOYLE AND SON CALEB

KAM CHANCELLOR

Following the holdout of Seahawks safety Kam Chancellor reminds me of a time 35 years ago when the Seattle Sonics roster was loaded with young talent but suffered through a season without their leading scorer because he held out the entire season.

Like Chancellor, Gus Williams, a.k.a. “The Wizard”, was 27 years old and in the prime of his career. He’d led the Sonics in scoring during their 1979 world championship series victory over the Baltimore Bullets with an average of 28.6 points per game and during the following regular season (18.7/game).

Gus was a six-foot-two speed burner who often seemed like a one-man fast break, but he was also an unselfish distributor of the ball and regularly set up his teammates for easy baskets.

But, word was that Williams, who was under contract for $500,000 for the 1980-81 season, wanted a new five-year deal worth 2.5 million along with many other high-priced benefits while the Sonics were offering a one-year deal for $800,000.

So, in much the same manner that Chancellor has reportedly dug his heels in, Williams did as well.

When the Sonics won the championship in 1979 they looked like a potential dynasty in the making. Their starting backcourt of Williams and finals MVP Dennis Johnson were only 25 and 24-years old respectively. Starting center Jack Sikma and bruising power forward Lonnie Shelton were each only 23.

But, by the time the 1980-81 rolled around, Dennis Johnson had been traded to the Phoenix Suns in exchange for all-star guard Paul Westphal and Williams was a holdout. Johnson and Coach Lenny Wilkens didn’t see eye-to-eye and Johnson was sent packing. The team’s spiritual leader and rugged rebounding forward, Paul Silas, had also retired.

Shortly after the season began, the team lost Shelton to a season ending wrist surgery and before the season was over Paul Westphal suffered a foot injury that caused him to miss 25 games.

As Sikma said, without Gus their transition game disappeared and they became a different, much slower team, one that seldom got any easy baskets.

A team that had gone 56-26 during the regular season the prior year and advanced to the conference finals before losing to a Los Angeles Lakers team led by rookie Magic Johnson fell all the way to 34-48.

Ultimately, Williams signed a new five-year $3 million deal once the disastrous season was completed, and the team rebounded to a 50-game winning season the following year, but it was the Lakers franchise that went on to become the dynasty of the 1980s.

Now Seattle has another potential dynasty in the making, a Seahawks team full of young talent and promise for years to come, but the question is whether or not they’ll be able to keep that core together. General Manager John Schneider has seemingly done a remarkable job of it so far, but no sooner does he lock up one or two guys and another one starts complaining about his own salary.

I don’t know all of the specifics of Chancellor’s current deal, nor do I care to. I read that former Seahawk turned television analyst Michael Robinson says that Kam feels he’s worth more than the four-year $28 million dollar contract extension he signed in 2013.

Well, maybe he is, I don’t really care. To my way of thinking when a fellow agrees to a deal he should live up to it and what anybody else is signed for over the course of that deal is irrelevant.

Whatever happened to living up to a bargain? And why is this type of thing seemingly always a one-way street? We constantly hear about players wanting a new deal for more money because they think their performance warrants more than their current contract calls for.

Well, what about all the underperforming players? How come we never hear about any of those guys offering to redo their contracts to play for less money because they’re clearly not worth what they’re being paid by their teams?

Maybe there have been more examples of players insisting on a pay cut for their poor performance, but the only time I can recall it happening was in 1959 when Ted Williams failed to hit .300 for the Boston Red Sox for the first time in his career and finished at .254. Reportedly, Williams decided to play one more season but insisted his pay be reduced from $125,000 to $90,000. He then proceeded to come back and hit .316 the next year.

I love Kam Chancellor’s game on the field, but I’m tired of hearing about all these guys who sign multi-million dollar contracts and then start whining to the press about being worth more and insisting their contract be redone prior to their expiration.

As much as I’d like to see this issue resolved and Chancellor back on the field, I’m hoping the Seahawks dig their own heels in and refuse to redo the existing agreement.