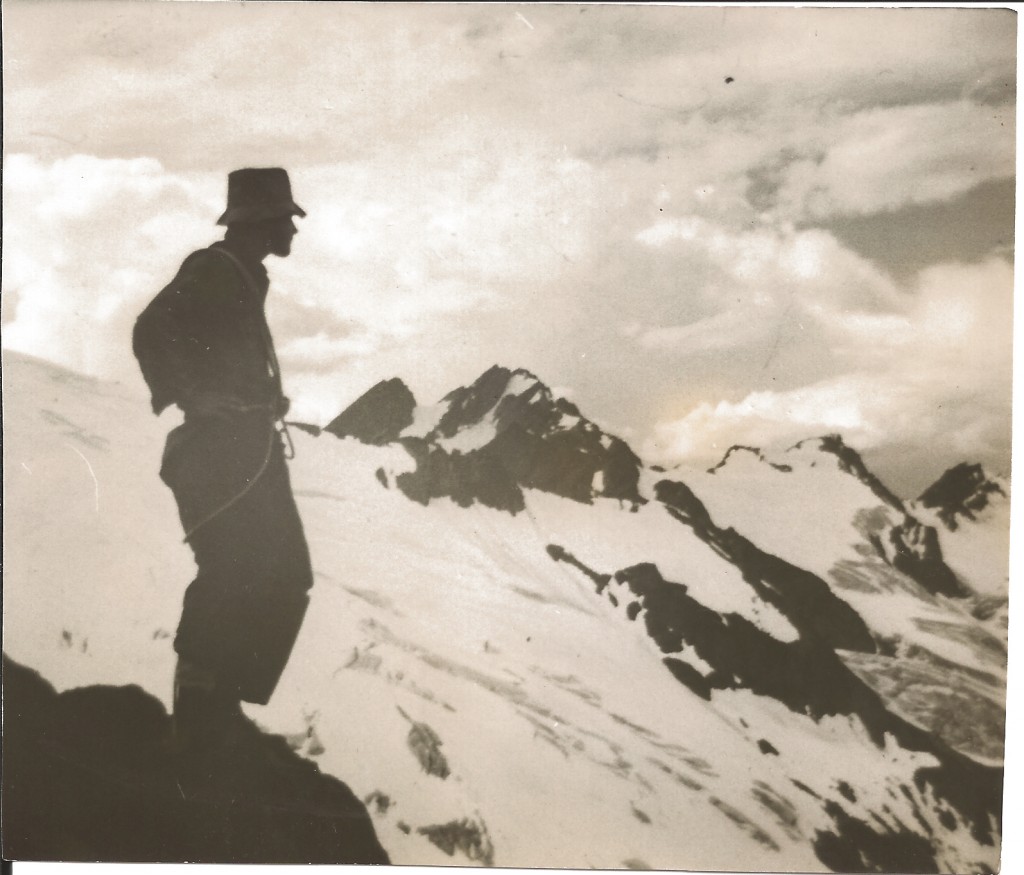

Kent Heathershaw in Andes in Peru

By Terry Mosher

Editor, Sports Paper

Kent Heathershaw for many years to count was an integral part of the outdoors community as the head of the mountaineering program at Olympic College. If you wanted to learn how to climb mountain peaks and do it safely, chances are you learned from him.

But that is not the complete Heathershaw resume. He also was ski instructor at OC and taught art and other subjects when needed, coached tennis at West Bremerton-Bremerton High School.

Heathershaw, who lives in Southworth, also continues to hike and camp and climb and play tennis at the age of 84. Just this past weekend he was climbing Lake Angeles, a modest climb of about 4,000 feet.

“We were up there surrounded by two to three goats,” says Heathershaw.

He went hiking the weekend before that with his grandkids north of Hoquiam and along the beach for several miles and then camping.

Heathershaw and the wilderness, the woods, and the mountains go together like bread and butter. He belongs to the outdoors as much as the mushrooms, the bears, the deer, and moss growing on old growth trees. And his presence in the outdoors started at a young age

“I started working when I was about 15 years old for the U.S. Forest Service,” says Heathershaw. “I was the lookout for about three different years in the summer in the northwest corner of Washington, and I did it in a couple places in Idaho.”

Lookout towers began to be built in the early 1900s because of The Great Fire of 1910 that consumed 3,000,000 acres in Washington, Idaho and Montana. The lookouts were usually built at the peak of mountains to give the person in the lookout a maximum view to spot fires and either put them out themselves or to alert fire personnel.

“You usually had a stairway (to the tower) and an (Osborne) Fire Finder (that determined the angle to the fire),” says Heathershaw.

His work required him to be alone in these towers for three months at a time over a summer. He would be supplied every so often by a pack train.

“They (the towers) were probably eight-feet square,” Heathershaw says. “It’s pretty exciting up there. During storms all the nails would turn blue because of lightening. I’d lay on the middle of the floor (to avoid touching any medal) until the lightening passed by.”

Heathershaw uses “pretty exciting” a lot while discussing his many mountaineering adventures to various parts of the world in 15 different countries. It’s his way of expressing the danger of those experiences, and a way of almost dismissing those dangers, as in “it was pretty exciting.”

You and me would probably used far different words, as in “let’s get the (blank) out of here.”

Heathershaw graduated from Lewis and Clark High School in Spokane in 1947 and went on to college at Eastern Washington where he got two degrees, one in education and the other in fine arts.

He became an illustrator for numerous books, including the “Climber’s Guide to the Olympic Mountains (which has recently been renamed “Olympic Mountains: A Climbing Guide”) of which he is one of the authors. He also has been a life-long painter.

Heathershaw was not a sports guy in high school, but at Eastern tried out for the baseball team and played tennis for the school and has shown over the course of his life that he has excellent athletic ability.

He probably inherited some of that athletic ability from his dad – Earl Heathershaw – who was a pitcher and played minor league baseball in the then Brooklyn Dodgers’ organization with the Spokane Indians.

“His wife didn’t like baseball so he had to quit,” says Heathershaw. “There wasn’t much money in baseball in those days.”

Heathershaw started playing tennis at Eastern when he was a junior. He went undefeated as a senior while playing No. 2 singles behind Jack Dunn, who was from Bremerton. He and Dunn won the conference doubles championship in his senior year.

After graduating from Eastern Washington in 1951, Heathershaw was taken into the Army (he served from 1951-53), and was sent to intelligence school at Fort Holabird in Maryland. Thus equipped, Heathershaw was sent to Korea where he served as an intelligent officer during the Korean Conflict.

“We gathered information on enemy forces,” says Heathershaw, “and what tactics they were using.”

The information gathered was mostly about the Chinese, who had entered the fray in October of 1950.

“They outnumbered us something like eight to one,” says Heathershaw.

When he came back from Korea he used the GI Bill to go back to Eastern Washington for a year to get his second degree, this in education in 1955. He then taught for the 1955-56 school year at Shelton High School where he played on a semi-pro basketball team.

Bob Fredericks, a friend and longtime Bremerton activist in the local sports community (also a founder of the Bremerton Tennis & Athletic Club; now the Kitsap Tennis & Athletic Center), jokes about Heathershaw playing against and guarding the great Johnny O’Brien in one basketball game.

“Kent held him to 40 points,” Fredericks says.

“It was the other guard’s fault,” laughs Heathershaw.

After one year at Shelton, Heathershaw got a job teaching art at Bremerton’s West High School in 1956 (the first year West High opened its doors). And for 20 years he was the tennis coach at the school, winning several Capitol League championships.

It was while he was at West an Olympic College administrator, George Martin, recruited him to take over the mountaineering program at the college. Little did anybody know at the time this would be the start of something good, and that Heathershaw would last as the head of the program for 40 years before retiring.

For the first 30 years he taught OC mountaineering as a part-time job while he continued teaching at West High/ Bremeton High School (1978 West and East merged back to Bremerton HS). When he retired teaching at the high school he began teaching art at OC along with his mountaineering and ski classes.

The mountaineering program evolved over the years to where he enlarged classes in backpacking survival and pushed out from basic mountaineering to advance mountaineering.

“I think I had more students than all the other PE teachers,” said Heathershaw, who never had a student suffer a major injury unless you consider bee stings major. But then Heathershaw had plenty of experience. Before he began taking over the mountaineering program at OC he had interrupted his teaching to enter the University of Oregon for its masters program.

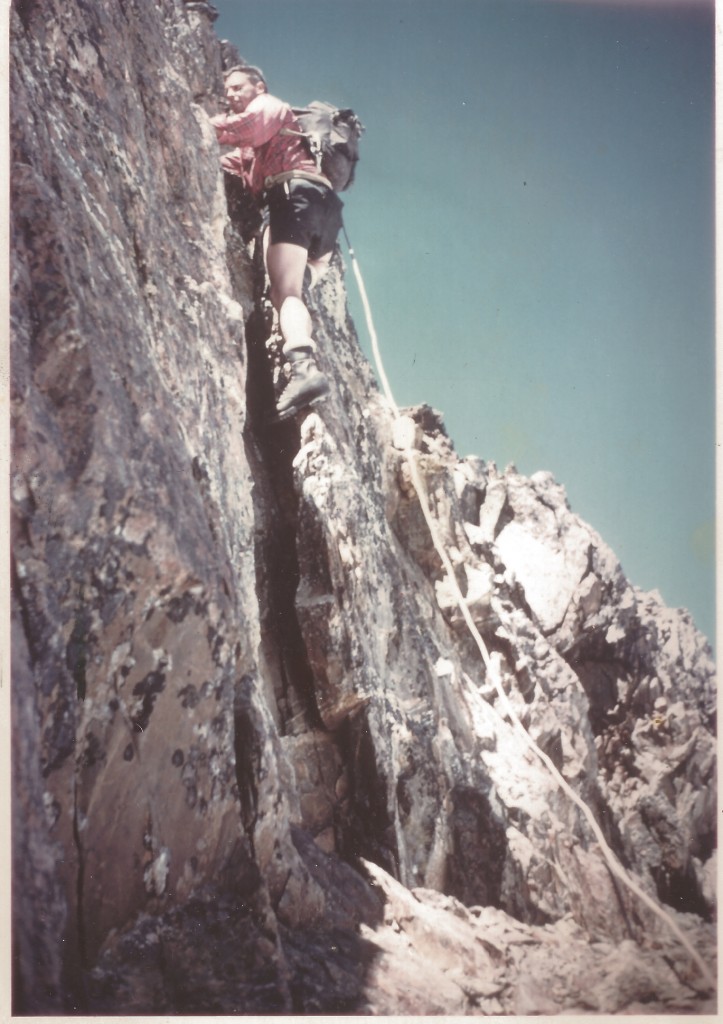

Kent Heathershaw near summit of Mt. Olympus in Olympic National Park

He spent two years in Eugene at the University of Oregon and extended out to what he was used to as a kid ‑ camping, fishing and hunting with his parents in northern Idaho – to mountain climbing in Oregon.

He climbed in Oregon, among other peaks, Mount Washington and Mount Thielsen. That would be the start of him climbing over 200 mountain peaks (12 of them a first-time ascent) around the world, including the Matterhorn in Switzerland.

“Do you know that the first man to climb the Matterhorn was an artist (Edward Whymper, whose successful attempt occurred July 14, 1865, although on the descent four of the climbers died)?” says Heathershaw. “It was just marvelous. There isn’t any place like it. You are above the timberline and there are rocks and snow and ice. (he laughs). That is real exciting.”

His quest to climb was taken to new heights when one summer he did 30 peaks in British Columbia.

He also has climbed Mount Rainier a total of 22 times.

“I have always climbed it as the leader,” says Heathershaw. “I took my students from OC up there.”

Along about 1972 he joined the Olympic Mountain Rescue, a vital program for the West Sound area due to the all the hiking and climbing avenues available to those willing to add, as Heathershaw would say, excitement to their lifes.

Kent Heathershaw on top of an unclimbed peak in the Andes in Peru

His climbing expeditions include going to South America three times. It was in the Andes in Peru where he lost his toes.

Yup, that’s right, he lost all his toes.

That climb started when he discovered a mountaineering club at the University of Minnesota was claiming to be the only such club at a college in the United States. He begged to differ and wrote them a note saying Olympic College had a mountaineering program 10 years before they did.

Impressed, they wrote him back and said they were planning a climbing trip in the Andes in Peru, needed an experience climber to lead them, and asked if he was willing to go. That was like asking a sugar addict if he wanted a glazed doughnut stuffed with cream.

“I had a different pair of boots,” says Heathershaw. “They were kind of a large black boot. If you remember what Mickey Mouse boots looked like, they looked like that. I had them in Korea. They were thermo boots and I thought they would be great for climbing.”

So he took them on the trip.

Those boots became the center of the problem that followed.

“What happen is I came down with pulmonary edema at 18,000 feet and at that attitude you are not always aware of the things happening to you,” Heathershaw said. “I went to bed with my boots on and my feet froze during the night. I don’t think I ever slept with my boots on.”

Thermo climbing boots absorb moisture, so climbers when they camp at night take their boots and socks off. The socks are normally drenched with moisture and some climbers dry them by placing them on their chest while they sleep. The problem was because of the edema, Heathershaw wasn’t thinking clearly and fell asleep with his boots and socks on, and during the night the socks froze to his feet. His feet, Heathershaw says, were frozen up to his ankles.

Heathershaw couldn’t walk, so he was placed on a tarp and was dragged down the mountain.

“It was downhill all the way,” says Heathershaw, joking about the descent. ““We were on a glacier, so it went pretty well.

He was rushed to a hospital in Lima where he would stay for the next four months.

“A couple of the doctors wanted to amputate both legs,” says Fredericks. “They thought that was the only way to save him.”

“They felt they might have to take off both feet,” Heathershaw said, “but what happened they fortunately got a doctor who had been trained in Boston and he said to wait and them the feet thaw out for a couple weeks and see if the circulation comes back.

“It was a little painful (that is Heathershaw-speak for hurting like the devil), but they thawed and the circulation was really good.”

The fact Heathershaw was a climber and in good shape worked for him, although they eventually had to take off his toes.

During rehab Heathershaw had to learn how to walk without toes by, among other things, climbing up steps and by hitting a tennis ball against a wall. Heathershaw was quickly up and hitting a tennis ball against a wall to learn how to keep his balance while playing tennis. The big toe controls movement and balance, so it wasn’t easy, but he did it. And when he did get back on the court at the Bremerton Tennis & Athletic Club (now renamed Kitsap Tennis & Athletic Center) he played as well as he always did.

“The guys who played tennis said they didn’t see any difference,” Heathershaw said, then laughing he added, “They said the operation was done at the wrong end.

“I remember from kinesiology (classes) when they talked about the structure of your feet and things like that and they said you can’t do anything if you lose your toes because you lose your balance. So I proved that wrong.

“A lot of people have lost their toes in mountaineering and everybody seems to do pretty well. “

Heathershaw was an OC ski instructor as well and he said the lost of toes didn’t set him back there either. He did find himself a bit slower on the tennis court, but in the bigger picture there wasn’t a lot of difference.

“The thing I found I couldn’t do was single skiing on a water board,” he says, “because losing your big toe does make a difference water skiing. “

He has twice come down with pulmonary edema while climbing. The one in Peru and again on Alaska Mount McKinley at about 18,000 feet.

“Some people are slow to learn,” laughs Heathershaw,.

To get Heathershaw off Mount McKinley so he could be helped, a bush pilot plane was sent to pick him up. It landed on a glacier, but in order for the plane to take off it had to be turned around and then pushed to get a start.

As it rolled down the glacier, “we jumped into the cockpit and got it airborne,” says Heathershaw.

“So that was kind of exciting,” he says.

As everything mountain climbing seems to be for him, including the time he was in New Zealand on a ski tour and sign up with several others to climb into a helicopter to fly to the Tasman Glacier at 3,000 feet on Mount Cook and then ski off.

“It was pretty difficult,” says Heathershaw.

The snow was powdery and about ankle deep, covering his skis so he had to be extra alert to complete the journey.

Dangerous?

Sure.

Exciting?

You bet.

The excitement now for Heathershaw is to plan weekend camping trips with his two young grandkids and friends.

“I’m always trying to do something, “he says.

As long as it’s exciting, he’s good to go