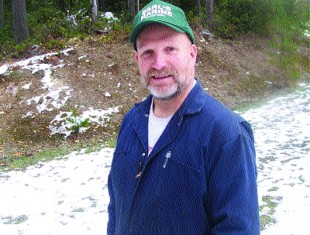

BOYD MCCASLIN, 2009

Editor’s Note: The story below first ran in The Sports Paper in December of 2009. It is being reprinted because of the death of Boyd McCaslin on July 1 in Hayward, Calif. McCaslin was 87 when he died.

By Terry Mosher

Editor, Sports Paper

Another wisp of Bremerton’s sporting past lives on in California, recounting the good memories of that past. Boyd McCaslin, son of a toughie named Louis Charles McCaslin in official papers but Boy McCaslin when he was punching the lights out of fighters all through the Pacific Northwest, has a clear memory of the old days that belie his 84 years of age.

“I was born in 1925 at Harrison Hospital, which was on Chester (Avenue) in Bremerton,” said McCaslin from his home in Fremont, Calif. “Now it’s some kind of apartments for older people, I believe.”

Long before McCaslin, who has lived in Fremont for the last 49 years, turned to retirement and a golfer’s life chasing after that little white ball, he came out of the blue as a basketball player. He wasn’t quite good enough to be a star under Hall of Fame coach Ken Wills at Bremerton but continued to develop and as a late bloomer played college ball at Dartmouth and then Michigan before starting a career in coaching that lasted for many years and included an early stop at Bellingham where he coached the Red Raiders to five straight wins over Wills-coached Bremerton teams.

He wound up coaching basketball at Arroyo high school in California where in 1966 his team shocked northern California by winning a state championship over a talented and heavily favored McClymonds team at the University of California’s Harmon Gym in Berkeley.

We are getting ahead of the story, however. It’s a story that included McCaslin living in his early years in a little shack on the ferry dock in Port Orchard. This was before the state stepped in to take over the ferry system.

“My father was the agent on the ferry boat for the Black Ball Line,” says McCaslin. “The ferry used to go from Seattle to Bremerton and then Port Orchard. I lived in Port Orchard until 12. We lived on the end of the dock. My father and his brother-in-law built a building, not much more than a shack. It was more like a shoebox. It didn’t have a bathroom. We had to use the public bathroom.”

When McCaslin’s father wasn’t working for the ferry system, he was making a little cash as a pro fighter. Results for Boy McCaslin, a welterweight, are sketchy, but he did fight a guy named Enrique “Battling Zuzu” Zuzuarregui five times in the 1920s, winning two by knockout, losing two by knockout and drawing once. At that time, Boy McCaslin had a 9-5-1 record.

Boy McCaslin also knocked out Sailor Marvin in the first round in a 1920 bout held at the Community House in Charleston (West Bremerton).

“They used to have fights in Bremerton and all around the Northwest,” says McCaslin. “The fans loved him. He just tore at the other guy and gave all he had. He had around 105 fights.

“He quit fighting just a little bit before I was born. I know one time he was suppose to have a fight for the Pacific Welterweight Championship, but got a severe case of the boils and never followed up on it.”

The McCaslin’s eventually moved to Bremerton and lived on Lincoln Avenue. Bremerton was beginning its World War II bloom (its population would go over 80,000) and led to the Golden Age of Bremerton athletics. Many of those excellent athletes like Don Heinrich and Ted Tappe were part of the Warren Avenue Gang, although McCaslin was not.

“I knew all those guys, but I wasn’t a part of the gang,” McCaslin said. “But we used to roller skate and play roller hockey on the tennis courts there.”

The old Bremerton High School used to be between 4th and 5th Street and McCaslin said that when the school was built at its current location, he helped build it.

“In 1943, I went t the Labor Union downtown and told them I wanted to work as a laborer,” McCaslin said. “They set me to work building the school over in Manette. Then they started building the high school and I asked if I could transfer over there because it was closer to home. I was making $1.13 an hour and got time-and-half because I worked six days a week.”

Before that, however, he found basketball.

With a little help from the custodian staff.

McCaslin made a deal with a custodian at the school that allowed him to get the keys to the gym so he could shoot around in the gym in the morning before school officially started.

“They had these plywood cutouts of policemen they placed in the street to get people to slow down and I would get up early in the morning, go to school and get those cutouts and put them out,” McCaslin said.

In return, he got entry to the gym.

Those early-morning shoot-arounds in the gym would eventually pay dividends for McCaslin. But they didn’t show up in high school. While he played for Wills, he was not a big star. But he did realize Wills was far ahead of what other coaches were doing.

“There were so many kids who wanted to play basketball,” McCaslin said. “ He had two freshmen basketball teams. One was blue and the other was gold. There were 15 players on each one. And he had a “B” team made up of sophomores and then there was the junior varsity team and the varsity team.”

McCaslin played on a freshmen team, on the “B” team as a sophomore and was on the junior varsity as a junior. He was on the varsity as a senior, but didn’t play a whole lot.

The best basketball for McCaslin was yet to come.

In the meantime, Wills continued to develop what became a state power program by spending much of his time enticing kids to play the sport. He opened the gym at 1 p.m. on Sunday’s so as not to interfere with church services and kids would flock to the gym.

“The kids were really into basketball,” says McCaslin. “It was fun to be there. And Wills had so much energy. There was no stopping him. And he loved to play himself. Joe Stottlebower and myself, we would play Wills and his assistant Tinny Johnson in the springtime when the gym was empty. We had fun doing that. We held our own against them.

“Darwin Gilchrist used to play Wills. Gilchrist was such a competitor; he wasn’t going to be beat. And Wills was pretty much the same way. Wills got so ticked off at Gilchrist, he told him he wasn’t going to play him anymore because he was so aggressive.”

Gilchrist became an all-state player at Bremerton, played at Olympic College, Long Island University (LIU) and Puget Sound. He lives in Manchester.

Stottlebower went on to make the 1944 All-Tournament team at state.

“Joe was a very good high school player,” says McCaslin. “I was just a guy trying to do my best I could and learn.”

McCaslin never quit learning. Even when he was in college, he would come home for the summers and quickly go over to Wills’ home, get the keys to the gym, and practice his game for hours on end, sometimes all by himself.

“I would do that all summer,” McCaslin said. “I was getting ahead of everybody else by just playing more than anybody else.”

While he was helping build the high school during the summer of his graduation, World War II droned on and when it became clear he was going to be drafted in the Army, McCaslin choose to enlist in the Navy.

He got into the Navy’s V-12 Officer Training Program, and was sent to Hobart College in Geneva, N.Y, along Seneca Lake in the heart of New York’s Fingerlakes. McCaslin played college basketball there for a year.

When the war started winding down, the Navy closed the V-12 program at Hobart. The Navy sent half of the students in the program to Cornell and the other half to Dartmouth, which is where McCaslin was sent.

That move turned out to be fortuitous because the 6-foot-2 McCaslin was coached at Dartmouth by Ozzie Cowles, who would later become instrumental in him moving on to the University of Michigan.

“It was just by chance I went to Dartmouth,” McCaslin said.

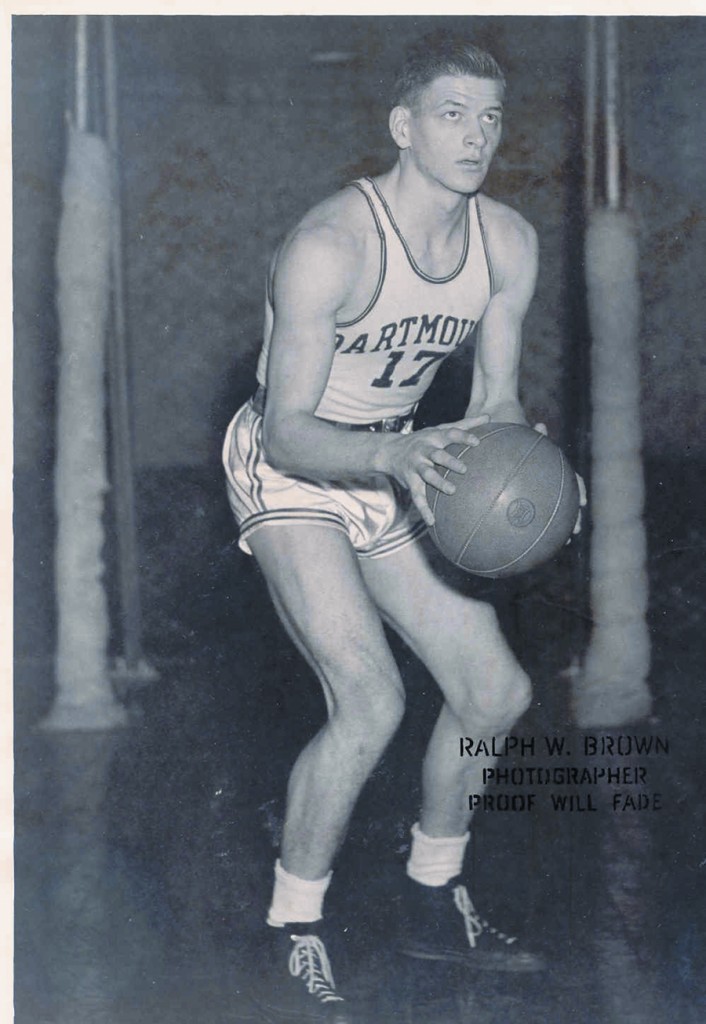

BOYD MCCASLIN, 1946

By the time he got to Dartmouth, the team had been practicing for a week. He talked to Cowles, who wasn’t the most receptive to having a new player, but offered to let McCaslin come to practice that night to see what he had.

McCaslin realized he was up against it so he gave it everything he had, hustling, rebounding and playing the kind of tough defense Will had insisted from his players. When practice was over, McCaslin started to leave when he heard Cowles calling to him, “Hey Boyd, hey Boyd, come over here.”

“Coweles was only about 5-8 or 5-9 and I was 6-2 and he stood in front of me, looked up and said, ‘I think you got what I want.’ You can imagine I was walking on air.”

He played basketball for The Big Green just one year, making second team all-conference. In one game against Cornell, McCaslin and the team’s center combined for 32 points – 16 each – in a 48-44 victory.

“I could shoot the darn ball,” McCaslin says. “I had a really good shot, and I could rebound and hustle.”

McCaslin decided in March of 1946 that with the war over he no longer wanted to be in the Navy’s V-12 program. He was transferred to Sand Point Naval Station in Seattle, checked in and then took the ferry to Bremerton and went to PSNS where he signed his discharge papers. He then went home.

He didn’t know what he was going to do. McCaslin had just been a very average player in high school, so it wasn’t like he was high on any college list. After a couple months, he got a letter from an attorney in Seattle who was a University of Michigan alumnus. He was recruiting people and offered McCaslin $200 to go back to Michigan.

McCaslin thought why not? He then talked Stottlebower into doing the same thing. But before McCaslin left, he received a letter from Cowles, asking him to come back and try out for Michigan. It turns out, Cowles was the new Michigan coach.

Although McCaslin almost was not admitted to the school, when he did get in he quickly became a starter, passing up Stottlebower, who was a better high school player. He remembers scoring 19 points the first time playing against Michigan State in a Michigan uniform.

McCaslin would go on to play three years, helping Michigan to the Big Nine championship and the Wolverines first NCAA Tournament in his second year. Cowles left for Minnesota after that second year. Cowles was a Carleton College (Minnesota) graduate, so it was natural for him to go back to Minnesota, although there was another consideration.

According to an Internet story on the history of Michigan basketball, when the Wolverines returned from the NCAA Tournament, Cowles ran into a situation that closed the deal for him.

“We’d been gone for a week, but no one seemed to notice,” Cowles said. “A couple of days after we got back, Fritz Crisler (Michigan athletic director and head football coach) stuck his head in my office and asked me where I’d been. That was when I decided that Michigan was no place to coach basketball.”

After the 1949 basketball season, McCaslin and Bob Harrison would be selected to play against the Harlem Globetrotters before 14,000 at the old Chicago Stadium Harrison was a 6-1 guard who played nine years in the NBA with the Minneapolis Lakers, Milwaukee Hawks, St. Louis Hawks and the Syracuse Nationals.

“In the dressing room before the game, we asked each other what we were going to do,” McCaslin said. “We all agreed not to let them horse around. We played our butts off and by God if we didn’t win the game, 51-50.

“That was in March of 1949 and the Globetrotters had just beaten the Minneapolis Lakers, which had George Miken.”

McCaslin would be on teams in Bellingham in 1953 and 1954 that also beat the Globetrotters western team. Those winning teams were comprised of coaches and top players around the state, including Gale Bishop, who played one season in the NBA with the Philadelphia Warriors, who McCaslin said was a great player.

After graduating from Michigan, McCaslin became a teacher and head basketball coach at Wayzata High School in Plymouth, Minn. for two years and then, with Cowles’ help, landed the head coaching position at Watertown, S.D. He was there two years and took both of his teams to the state tournament.

In the last seconds of a game they lost at state in the second year, Watertown played with six players on the floor, and got away with it.

When McCaslin gave speeches at various functions that school year, he always mentioned that game. He would tell his audiences, “I saved a lot of coaches’ jobs that year. All they had to do is tell their superintendents that McCaslin couldn’t win with six players on the floor, how do you expect me to win with five? They all got a kick out of that.”

McCaslin then got the job at Bellingham. The Red Raiders were playing in the Cross State League with Bremerton and prior to his arrival, Wills-coached Bremerton teams had beaten Bellingham 14 straight times over seven years.

That all changed under McCaslin.

“My first year was the 1952-53 season and we beat Bremerton in Bellingham, then in Bremerton, won the Cross State League and made the state tournament. McCaslin’s team beat Richland 71-46, then was beaten by Longview, 59-50. They bounced back to beat the Jud Heathcote-coached West Valley of Spokane team, 59-57 in overtime and then clipped Wills and Bremerton again for fourth place, 45-42.

McCaslin left Bellingham in 1960 to teach math and be the head coach at Arroyo in San Lorenzo, Calif. He spent 25 years there, retiring from coaching in 1983 and teaching in 1985. It was in the early years that McCaslin had several solid teams, including the one in 1964 that went 24-2 and won the Tournament of Champions, an annual event at the University of California that attracted huge crowds. It brought together all the different league champions and was usually won by powerful McClymonds.

“McClymonds, which is in Oakland, at one time had won the tournament six times in a row,” McCaslin said. “They were powerful and I didn’t know if we could stay with those guys.”

Even now McCaslin describes the 55-53 victory over McClymonds as,” Just a wonderful win. The most valuable player was Steve Desimone, who is the golf coach at California. Their team played (recently) at Gold Mountain (in the Pac-10 championships).

“(Desimone) is a heck of a guy. He was 6-1, left-handed, and could shoot.”

McCaslin doesn’t do much of anything anymore. He hasn’t played golf in a year. He cuts the grass and looks after his wife of 58 years, Darlene, who is battling brain cancer.

“I take care of her now,” says McCaslin. “I don’t know how it will turn out.”

They have three sons – Jim, Tom and Ted. Jim lives with his family – which includes daughter Erin, the starting point guard for Tahoma High School – in Maple Valley, Wash.

“She is a tremendous shooter,” McCaslin says of his granddaughter, “and a chip off the old block.”

It’s a good block to be a chip of.